Nearly every Australian ADI is heavily exposed to the Australian mortgage market with 60% of total banking assets being residential mortgages within Australia. This exposure to domestic residential real estate is 20% more than the second most exposed country being Norway, double the US percentage and four times the ratio in Hong Kong where banking system exposure is 14%[1].

The largest threat to any bank’s credit-worthiness is bad debts and therefore the largest risk to both the system and nearly every individual ADI in Australia is residential mortgage defaults; hence an understanding and view on potential threats to the housing market that might cause defaults to rise is a key consideration to any investor wishing to manage risk. Amicus provided such an update to its clients at the end of November.

The key considerations in assessing the risk are determining how far will house prices fall and at what point of house price falls do loan losses start to become a problem on bank balance sheets? Both answers are unknown; but there appears be two factors driving the housing market lower: the first being the well documented tightening of lending standards and the second is deteriorating investor sentiment.

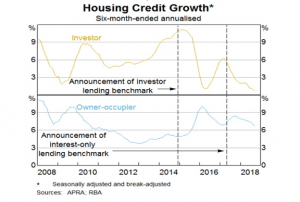

There is strong economic logic for this second factor partially driving the market being that if falls were due to purely a tightening of credit (lack of supply of mortgages) prices (mortgage interest rates) would be expected to rise, but this is not the case and in fact for desirable borrowers interest rates have actually fallen. No rational investor wishes to purchase an asset expected to fall in price and with further falls being the almost universal prediction, investors are now selling rather than buying. The graphs below support this conclusion.

As demand for investor loans have fallen, those for owner occupiers have risen. This is a positive long term development as it probably means an improvement in the quality of bank assets which will hopefully protect these banks in the coming downturn. The larger concern is the lower quality mortgages written earlier at the peak of the market as these are the ones most likely to cause issues.

Bank loan losses currently remain at historically low levels, but this is more a reflection of previously rising house prices than earlier good lending standards as any struggling borrower simply sells their house for a profit in a rising market as opposed to defaulting on a mortgage they can no longer afford. As a result, borrowers unable to afford their mortgage payments are effectively invisible.

The next six months are likely to be extremely interesting on two fronts. Firstly, whether the economy slows abruptly, as per the harbinger of the latest national accounts released at the start of December, and secondly whether loan losses begin to rise. When loans losses rise, it will most likely lead to a further tightening of credit standards by the ADIs and more negative sentiment exacerbating falls in a downward spiral.

Amicus argues this is probably a good time all investors who are not receiving professional advice from an independent advisor (as opposed to a broker or market operator who is motivated to keep selling product) to consider this as risks for holders of ADI securities in the form or term deposits and FRN’s are probably higher now than at any point in the last five years.

[1] Moody’s as at June 2017 in explaining their downgrading of Australian Banks